Creation Ex Nihilo: André

Malraux and the Concept of

Artistic Creation

I’d

like to investigate this topic via the

French art theorist, André

Malraux – a name that may not mean a lot to you because his work has

been

neglected in recent times. But Malraux developed a very powerful theory

of art

which, among many other things, includes an explanation of what

creation means

in the case of art, an explanation that I shall try to describe as

succinctly

as possible.

Malraux

was born in 1901 and died in 1976. He fought in

the Spanish Civil War and later against the Nazis in the Second World

War, both

in the army and in the Resistance, so, he was well acquainted with the

various horrors

the times. Together with a series of intellectual developments, the

events of

the 20th century, Malraux believed, had left

Western civilization

without any firmly-held belief in the significance of human existence.

God, he

agreed, was certainly dead, but that was not all. The Enlightenment had

replaced God with a faith in rational, civilized man, and that faith

was now

dead as well. The nineteenth century had developed a revised form of

humanism

based on science, progress and the ideal of new and better humanity yet

to be born.

But the 20th century had killed that too and now

nothing was left. So

as early as 1926, Malraux had written: “Absolute reality for us was

God; then

man. But man

is

dead, after God, and we are now engaged in an anguished

search for

something to which we can assign his strange inheritance…” (And this,

incidentally,

was some four decades before Foucault was edging towards the same idea

in his

book The Order of Things.) These

convictions

remained with Malraux throughout his life; so in 1957, for example, in The Metamorphosis of the Gods, he

describes the modern Western world as the first civilization that “is

aware that

it does not understand man’s significance”. Or as he put it elsewhere:

“Here is

the first civilization capable of conquering the world, but not of

inventing

its own temples or its own tombs.”[1]

But our

subject is art, so how does all this relate to art?

Well,

first of all, if man is dead, the aesthetic theories

– the philosophies of art – that depend on the ideals of man in

question are

necessarily dead too; and this is no small matter. The aesthetic

theories that

depend on Enlightenment notions of man are those of major figures such

as Hume

and Kant – theories that explain art in terms of familiar notions such

as

“judgement of taste”, “aesthetic sense”, “aesthetic pleasure” and so

on. And

the philosophies of art born of 19th century

concepts of man are

those that argue that art is tied in some systematic way to processes

of

historical change – which means the theories of such prominent figures

such as

Hegel, Marx, and Taine. If man is dead, those too are consigned to the

archives

of intellectual history. And along with all that, of course, go the

many

contemporary aesthetic theories – both analytic and continental – that

still

depend on these 18th and 19th

century foundations. Thus,

the consequences of the death of man in the field of art theory are

severe, to

say the least. The aesthetic theories of thinkers such as Hume, Kant,

Hegel,

and Marx, together with their modern descendants, are still of

historical

interest, but of historical interest only.

So, if Malraux has a theory of art – and he certainly does – where does he begin. If, as he says, we today know that we do not understand man’s significance, what foundation does he build on when he describes the nature and purpose of art? In short, if man is dead, where to now?

Malraux

discovered a new way forward during a particularly

dramatic experience in 1934 which laid the foundations for his thinking

about

art and for many other things as well. Unfortunately, time doesn’t

permit me to

describe the experience, but I can describe the thinking that resulted.

Malraux

found no answer to the question: What is man? On

that score he remained an agnostic – like most of us today, he

believes. But he

discovered something more fundamental: he discovered the primordial

human

capacity to pose the question at

stake. He discovered what he terms “the fundamental emotion man feels

in the

face of life, beginning with his own”[2]

and that emotion, he argues, is inseparable from the questions: “Why is

there

something rather than nothing?” and “Why has life taken this form?”[3]

This fundamental feeling of estrangement and perplexity, Malraux

argues, is at

the root of human consciousness itself. It is, simultaneously, an

awareness of

the world as a chaos of fleeting appearances and

of the possibility of resisting that chaos; it is an awareness

that everything, including man and all his endeavours, seems to be

without the

least significance, but at the same time an awareness of the

possibility of

conferring significance on man and his endeavours. In short, Malraux

discovered

the fundamental human capacity to call the world into question: a

capacity, if

not to understand man’s significance, at least to ask that question

and, in so

doing, to be more than a blind victim of meaninglessness and chaos.

This

discovery gave Malraux the answer to two crucial

questions. It explained the nature of an absolute, and it also

explained the

fundamental nature of art.

An

absolute, he argues – such as a religion or even a

powerful secular ideology – reveals an underlying unity beneath the

chaos of fleeting

appearances; it provides a definitive

answer to the questions: “Why is there something rather than

nothing?” and

“Why has life taken this form?”[4]

A Christian, for example, might answer that the world is the way it is

because

it is the will of the Creator God; a secular ideology might answer that

the

underlying meaning is to be found in History – with a capital H – which

is

moving towards an ultimate goal, such as a classless society. And, of

course,

there have been many other responses.

Then what is art? Art, Malraux

replies, also replaces

chaos with unity but, unlike an absolute, it gives no definitive

answers.

Art responds to the same

fundamental emotion I have described, but it does so by creating

another world, a rival world,

not

necessarily a supernal world, or a glorified one, but nevertheless a

unified

world – constructed solely of elements that, are the way they are, and

are

present,

for a reason. Art, Malraux writes, creates a world “scaled down to

man’s measure”.[5] It “wrests forms from

the

real world to which man is subject and make them enter a world in which

he is

the ruler”.[6]

All

this may seem rather abstract – and it inevitably is,

because I’m dealing with fundamental issues. Nevertheless, we see at

once that

the foundations of Malraux’s theory of art are very different from

those of

traditional aesthetics. There is no presumption, for example, that man

is

endowed with a certain “human nature” which includes an “aesthetic

sense” or a

“sense of taste” – both central Enlightenment beliefs. There is no

presumption

that man is a creature of historical circumstance and that History is

moving

towards a knowable goal. There is, in short, no absolute

that establishes man’s significance; there is only the

basic capacity, lying at the heart of human consciousness itself, to

call

creation into question, a capacity to which art gives a series of

answers, none

of them definitive. Art, Malraux writes, is “a series of provisional

responses to a question that remains intact”.[7]

Now,

abstract though they are, these propositions give

Malraux the basis for a comprehensive theory of art covering a range of

major

issues, one of which is the nature of artistic creation, the issue to

which I

now turn.

According

to one familiar view, which I’m sure you’ve all

encountered, the impulse to be an artist – the basic desire to paint,

to write,

or compose music – springs from a response to some aspect of what is

variously

called “the world around us”, or “reality”, or “life” – such as a

picturesque

scene in the case of a painter, an interesting person or incident for a

writer,

and perhaps a certain sequence of everyday sounds for the composer.[8]

Viewed in this light, the artist is first and foremost a person who

reacts to

“the world around him” or “reality” in an unusually sensitive way, and

then has

an urge to respond through some form of artistic expression. The basic

assumption is that the desire to be an artist, whether one succeeds or

fails,

springs essentially from a response to people, objects and incidents –

to “the

world”, “reality” or “life”.

Now, as

one might expect, given the ideas outlined above,

Malraux rejects explanations of this kind. Where

art is concerned, the “reality” or “life” that matters – the

reality that

art seeks to resist – is, as we have seen, the chaotic world of

fleeting

appearances – the meaningless realm in which man counts for nothing.

And

understandably, it not this reality – the reality to which man is mere

subject and blind victim

– that first fires an ambition to be a painter, writer or composer; it

is an

encounter with those objects in which

that chaos has been overcome,

those objects in which man is no longer mere subject, but ruler – that is, existing art.

The painter, in other words, is first

inspired by paintings, the novelist

by novels, the poet by poetry, and the composer by music. Malraux finds

ample

evidence for his claim in the history of art. “It is a revealing fact”,

he

writes,

that, when

explaining how his vocation came to him, every great artist traces it

back to

the emotion he experienced at his contact with some specific work of

art: a

writer to the reading of a poem or a novel, or a visit to a theatre; a

musician

to a concert he attended, a painter to a painting he once saw. Never do

we hear

of one who became an artist by suddenly, out of the blue, so to speak,

responding to an impulse to express some scene or startling incident.[9]

Not

surprisingly then, Malraux rejects the familiar view

that the artist is essentially the man or woman who is “more sensitive

to life”

than others, and that the urge to become an artist results from this

sensitivity. “An artist is not necessarily more sensitive than an

art-lover,”

he writes, “and is often less so than a young girl”. The artist,

however, has a

sensitivity “of a different order”. He or she is sensitive above all to

art: “Just as a musician loves

music and

not nightingales, and a poet poems and not sunsets, a painter is not

primarily

a person who is thrilled by figures and landscapes. He is essentially

one who

loves pictures.” There is, in other words, no necessary correlation

between

“being sensitive” in the everyday sense, and being an artist; and just

as the

supremely gifted artist is not necessarily unusually sensitive in that

everyday

sense, so, Malraux argues, “the most sensitive man in the world is not

necessarily an artist”.[10]

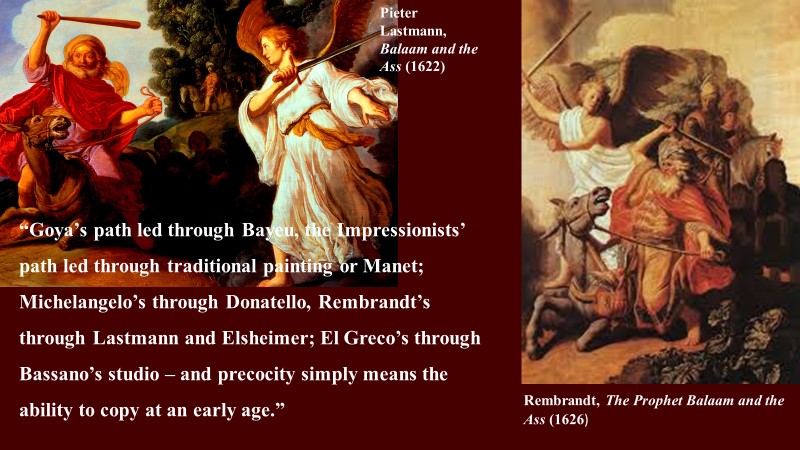

Malraux

then takes his thinking a step further. Given that

art, not “life”, is the artist’s point of departure, every great

artist, he

argues, “starts off with the pastiche”[11]

– that is by imitating the style of the artist or artists he

most admires, even if he is only vaguely aware of doing so. Again,

Malraux

argues, there is abundant evidence in the history of art:

Goya’s

path led through Bayeu,[12] the

Impressionists’ path led through

traditional painting or Manet; Michelangelo’s through Donatello,

Rembrandt’s

through Lastmann and Elsheimer; El Greco’s through Bassano’s studio –

and

precocity simply means the ability to copy at an early age.[13]

Genuine

artistic creation – as distinct from the pastiche

– occurs only when the artist senses that copying no longer suffices.

No longer

content with imitation, he begins to see, Malraux argues, that he is a

prisoner

of a style, and that speaking in someone else’s language “involves a

servitude

peculiar to the artist: a submission to certain forms and to a given

style”.[14]

Gradually glimpsing the possibility of a different unified world that

he or she

might bring into being, the artist starts to break free from the styles

that

had initially exerted such a powerful influence and begins, often

haltingly, to

develop another. Thus “it is against a style that every genius has to

struggle”,

Malraux writes; and “Cézanne’s architecturally ordered landscapes” (for

example) “did not stem from a conflict with trees and foliage, but from

a

conflict with painting as he knew it”.[15]

The

ideas of “struggle” and “breaking free” are important

here and the vocabulary Malraux employs in this context regularly

suggests a

striving to overcome, a search for deliverance. Paradoxically, he

argues, the

artist’s discovery of his or her own style involves a form of

destruction.

“What differentiates the man of genius from the man of talent, the

craftsman or

the dilettante,” he writes,

is not the

intensity of his responses to the world around him, nor only the

intensity of

his responses to the works of other artists; it is the fact that he

alone,

among all those who are fascinated by these works, also

seeks to destroy them.[16]

This claim, initially puzzling though it

seems, flows necessarily from the basic propositions we have

considered. If,

for the artist, bare “reality” or “the world around us” is merely the

chaos of

fleeting appearances, the painter (or composer or poet) has only two

choices: to “copy

another painter – or to make

discoveries”: to follow an existing path or to blaze

new

trails.[17] Thus, in fulfilling a desire to create – to

emulate the

achievements of the artist or artists he most admires – the painter,

composer

or poet must therefore, paradoxically, eradicate

from his own work all

trace of the styles of those very artists. That is, in bringing a new,

unified

world into being, he must struggle against and eventually destroy,

in

his own work, the very styles that elicited so much admiration and gave

birth

to the desire to be an artist in the first place.[18] There is no middle way, so to speak, – no neutral

path, such as a “styleless” representation of the world, in which the

artist

might take temporary refuge. The options are simply the pastiche or

discovery –

to copy or to blaze new trails.

The

proposition that there is no such thing as a

“styleless” representation of the world raises another issue we shall

consider

in a moment. This, however, is a good place to pause and consider a

possible

objection to the points made so far.

Perhaps

one might say to Malraux that in placing such a

strong emphasis on the impact of existing art, he gives the impression

that the

artist somehow works in a vacuum, oblivious to the objects, shapes and

colours

in the world around him. Surely the world of objects and events must

play some part in the creative

process? This

objection would oversimplify Malraux’s argument. He fully accepts that

the

everyday world can serve as a resource, a “dictionary” of forms, that

may be an

important source of suggestions and intimations. The issue, however, is

one of

priorities. “The outside world,” he writes,

can be

rich in suggestions – of colour, of line, and of the form the artist

“is after”

– for the artist who is looking for them, and on condition that he is

not

looking for them as for a pre-synthesised whole but in the sense that

great

wellsprings, their levels having built up, look for a watercourse to

follow as

a river. Under these conditions, the part played by living forms can be

immense; a vast “dictionary”, to borrow Delacroix’s term, will emerge

out of

limbo.[19]

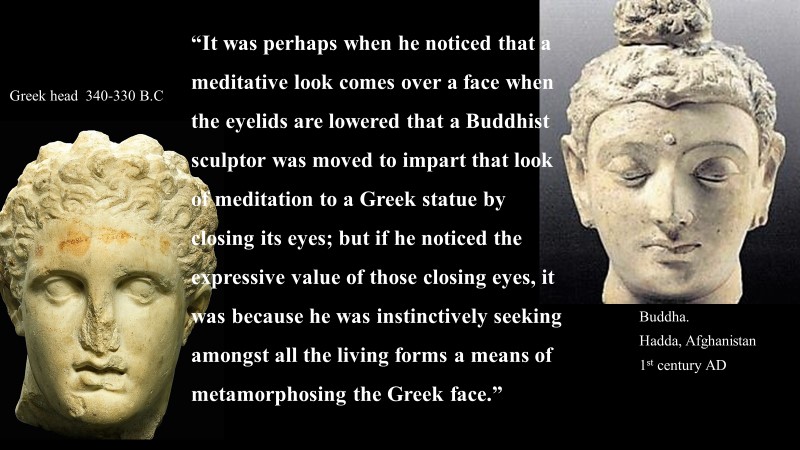

And

illustrating the point by a concrete example, he adds:

It was

perhaps when he noticed that a meditative look comes over a face when

the

eyelids are lowered that a Buddhist sculptor was moved to impart that

look of

meditation to a Greek statue by closing its eyes; but if he noticed the

expressive value of those closing eyes, it was because he was

instinctively

seeking amongst all the living forms a means of metamorphosing the

Greek face.[20]

What the artist rejects, in other words, is

not “the world” per se but the relationships

within the world, or

more accurately the absence of relationships –

their fundamentally

arbitrary and chaotic nature. The world of objects, shapes and colours

can play

a major role – but as servant not master. And the sine qua non,

if

it is to play that role, is the artist’s pursuit of a new unified world

as he

strives to break free from the styles that had initially impressed him.

“There

are rich treasures in the cavern of the world,” Malraux writes, summing

up the

point, “but if the artist is to find them he must bring his torch with

him”. [21]

Here,

if I may, I’d like briefly to return to Malraux’s

claim, mentioned earlier, that the artist has only two options: to

“copy

another painter – or to make discoveries”: to follow an existing path,

or to

blaze new trails. This proposition, we recall, arose from his argument

that the

artist begins with the pastiche and that, in bringing a new unified

world into

being, must struggle against, and eventually destroy, the style or

styles that

had originally impressed him and given birth to the initial desire to

be an

artist. On Malraux’s account, as we saw, there is no middle way – no

intermediate position, such as a “styleless” representation of the

world, in

which the artist might take temporary refuge. Now, in response to this,

one

might perhaps argue that Malraux is giving an unduly restricted account

of the

artist’s options. Surely, one might say, there are other alternatives

apart

from, on the one hand, the style of some previous artist (or some

combination

of more than one existing style), and on the other, a new style that

the artist

himself has discovered? Surely, there is some “extra-stylistic” option

– a

“neutral” position, so to speak, that can, at least temporarily,

provide

another path?

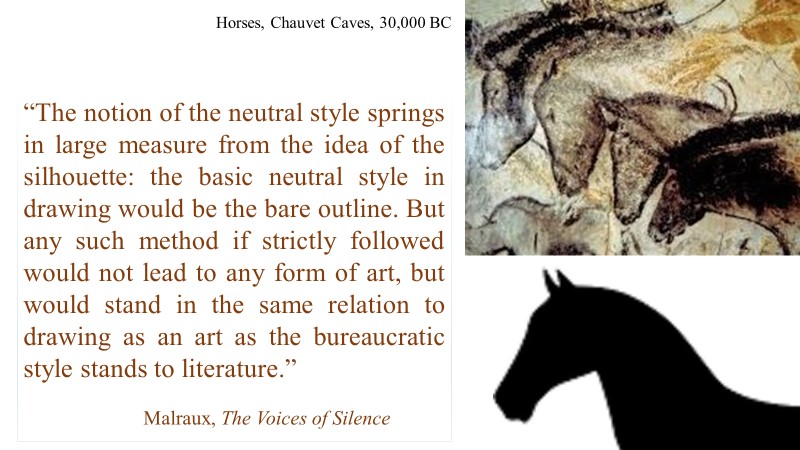

Malraux

calls this quite commonly held idea the “fallacy

of the neutral style”. In visual art, he writes, it is the notion

that there

exists a styleless, photographic kind of drawing (though we know now

that even

a photograph has its share of style) which would serve as the

foundation of a

work, style being something added.

The basis of this view, he continues, is

the idea that a living model can be copied “without any interpretation

or

expression”. But in fact, he argues,

No such

copy has ever been made. Even in drawing this notion can be applied

only to a

small range of subjects: a standing horse seen in profile, but not a

galloping

horse … Can one imagine a drawing of a rearing horse, seen from in

front, in a

style that is not that of any school, or of any innovator?

The notion

of

the neutral style, he adds,

springs in

large measure from the idea of the silhouette: the basic neutral style

in

drawing would be the bare outline. But any such method if strictly

followed

would not lead to any form of art, but would stand in the same relation

to

drawing as an art as the bureaucratic style stands to literature.[22]

The reasoning here flows directly from the

account of art we have been examining. If, for the artist, “the world

around

us” is at most a “dictionary” – an assemblage of elements combined in a

manner

that renders them incoherent – and if the artist replaces this with a

rival,

unified world, creation in art will always involve a process of

selection,

exclusion, and re-ordering – in short of transformation.

A “neutral

style” – that is, a procedure which, in the name of a supposed

“objectivity” or

“absolute realism” refused to transform – would

thus not be a

“styleless” art but no form of art at all. It would simply be an

abandonment of

the processes on which art necessarily depends.

Here we

see how far Malraux’s understanding of art differs

from the popular view that art is essentially a form of representation.

This

familiar idea, which is often invoked in the case of visual art and

literature

(though less so for music) fosters the belief that the art is

essentially a kind

of “transcription” of the outside world onto the surface of a canvas or

into

the pages of a novel. From there, it is but a short step to suggest

that a

neutral style, which would transcribe reality with minimum stylistic

“interference”, or even none at all, would be a possibility. Malraux’s

analysis

implies that this line of thought rests on a fundamental

misunderstanding. To

the extent that it is even conceivable, a neutral style would be a form

of

depiction that had abandoned all but the last vestiges of the

procedures

available to art. In visual art, it would result at best in the bare

outline or

the silhouette. In literature, it would lead to the commercial or

bureaucratic

style where, similarly, language tends towards a limited range of

standard, “lifeless”

forms. To the extent it were possible, a neutral style would, in other

words,

lead merely to the sign – that is,

to

those limited uses of visual forms or language that merely suggest, or

“point

to”, living forms (as a silhouette of a standing horse might be used to

indicate the presence of horses) but it would stop well short of portraying any such form.[23]

The artist, Malraux is arguing, is not involved in transcribing

anything, but

in transforming.[24]

Certainly, representation, in the simple sense of including in a

picture forms

resembling real objects, is one of the tools or techniques available to

art –

like the varied uses of line or colour – but, on Malraux’s account, it

is no

more than that. As a form of endeavour – as a human activity – he is

contending,

art is never representation. Art is

the creation of a rival world, a

world that depends for its existence on a process of transformation of

“the

world around us”. “We are beginning to understand,” he observes, “that

representation is one of the devices of style, instead of thinking that

style

is a means of representation”.[25]

“Great artists,” he writes, summing up this view, “are not transcribers

of the

world; they are its rivals”.[26]

It

follows from all this that, for Malraux, the true work

of art is a creation in

the full sense of the

term: it is something that seems to emerge “out of nowhere”, a creation

ex nihilo. This is not to deny

that in practice the process of

artistic

creation is often preceded by a laborious apprenticeship, and Malraux

himself

writes that “frequently the artist has to expel

his masters

from his canvases bit by bit; sometimes their hold on him remains so

strong

that he seems, as it were, to insinuate himself into odd corners of his

picture”.[27]

That said, however, the true work of art is a creation ex

nihilo because its achievement depends on the complete

destruction of the style or styles from which it originated, with no

intermediate position – no neutral position – to occupy. It’s for this

reason

that Malraux has so little enthusiasm for accounts of the history of

art that

are, to use his words, “only

chronologies of

influences”.[28]

For

Malraux, art, as distinct from the pastiche, begins precisely where

influences cease. While

acknowledging that every

artist begins by imitating, and that influences in this

sense are the crucible out of which art emerges, he is

claiming, nonetheless, that only when those influences have been

eradicated

does art comes into being. A history of art that spoke of artistic

creation

solely in terms of influences – either on, or by, the art it describes

– would,

for Malraux, speak of everything except the essential.

I said

at the beginning that I would say a few words about

why the topic of creation receives relatively little attention in

modern aesthetics

but I’ve left myself so little time I’ll need to keep my comments very

short. In essence,

creation fares badly,

in my view, because the two major sources of modern aesthetics –

Enlightenment

thought and nineteenth century thinkers such as Hegel and Marx – felt

their

prime concerns lay elsewhere. Enlightenment thinkers regarded art as a

given –

it was simply part of the human landscape they set out to explain – and

the

only question that mattered was how art could be linked up with the

models of

human nature they were developing. Hence the focus on ideas such as

aesthetic

sense, a judgement of taste, aesthetic pleasure and so on. For Hegel

and his

intellectual descendants, the situation has been similar, with the

important

difference that the idea of human nature they had in mind now included

the role

of history. Again, however, art was essentially a given – part of the

human

landscape – and the focus lay not on what creation might mean in the

case of

art, but on explaining the relationship between art and history. The

relative

lack of interest philosophers of art show in artistic creation today

is, I

think, a consequence of this historical inheritance. Modern aesthetics

is

heavily indebted to its 18th and 19th

century forbears –

more so than it often likes to admit – and this not only affects the

way it

thinks, but what it thinks about – and doesn’t

think about. Creation is art is a good example. It was

not high on the

agenda before, and it still isn’t now. For Malraux, by contrast, art is

not simply a given; he

explains its very

existence. Hence the important role creation plays in his thinking.

[1] La Métamorphose des

dieux, 37. Antimémoires, 7

[2] André Malraux, La Tête

d’obsidienne, (Paris:

Gallimard, 1974),

221. All translations from

French sources are my own.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] André Malraux, “Articles de ‘Verve’: De la

représentation en Occident et en Extrême Orient,” in Ecrits

sur l'Art (I), ed. Jean-Yves Tadié (Paris: Gallimard, 2004),

931-940, 933.

[6] Les Voix

du silence, 539.

[7]

Les Voix du silence, 887.

[8] In the case of music, the logic is sometimes

abandoned and it is suggested that a composer is inspired by scenes or

events

rather than sounds. This perhaps reflects an uncomfortable feeling that

a

sequence of everyday sounds seems an unlikely origin for a symphony or

concerto, for example. As Malraux puts it (also commenting on the

conventional view),

“A composer seems less likely to have become one out of a love for

nightingales

than a painter to have become a painter out of love for landscapes.” Les Voix du silence, 502.

[9] Ibid., 497. Malraux also neatly encapsulates

the point in a comment on the well-known legend about Giotto. “An old

story

goes,” he writes, “that Cimabue was struck with admiration when he saw

the

shepherd-boy, Giotto, sketching sheep. But, in the true biographies [of

artists], it is never the sheep that inspire a Giotto with the love of

painting, but rather the paintings of a man like Cimabue.” Les Voix du silence, 497. Cf. “No

shepherd became a Giotto by

looking at his sheep”. L'Homme précaire

et la littérature 125.

[10] Les Voix

du silence, 494.

[11] Ibid., 531.

[12] Francisco Bayeu (1734-1795), one of Goya’s

early teachers and mentors.

[13] Les Voix

du silence, 526. In a similar vein, Malraux writes in L’Homme précaire et la littérature:

“Rimbaud did not begin by

writing a kind of vague, formless Rimbaud, but with Banville; and the

same is

true, if we substitute other names instead of Banville, for Mallarmé,

Baudelaire, Nerval, Victor Hugo. A poet does not begin with something

vague and

formless but with forms he admires.” L'Homme

précaire et la littérature 155.

[14] Les Voix

du silence, 582.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid. Malraux’s emphasis.

[17] Ibid., 537.

[18] The idea can, however, be exaggerated. One

early critic argues that for Malraux “the artist … is essentially

demonic, and

his demonism is directed against the forms of his predecessors, which

he is

trying to devour…” John Darzins, “Malraux and the Destruction of

Aesthetics,” Yale French Studies 18

(1957): 108. This

distorts Malraux’s point.

[19] Ibid., 570. As he acknowledges, Malraux is

borrowing the term “dictionary” in this sense from Delacroix. (See Les Voix du silence, 570.) The thinking

here is not limited to visual art. In L’Homme

précaire et la littérature, Malraux uses the same concept of

a “Delacroix’s

dictionary” in the context of an analysis of literary creation. L'Homme précaire et la littérature 157.

[20] Les Voix

du silence, 573.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid., 534.

[23] As this analysis suggests, Malraux’s theory of

art provides no support for the claim advanced in certain “semiotic”

theories –

of which there are several variants – that art is essentially a system

of

signs. Malraux agrees that art occasionally makes

use of signs, but in itself the sign is, on his account, only

an embryonic

form of art. (See Ibid., 534, 543, 544.)

[24] Cf. “Whatever he might say, [the artist] never submits to the world, and always

submits the world to that which he substitutes for it. His will to

transform is

inseparable from his nature as artist.” André Malraux, La

Psychologie de l'art: La Création Artistique (Paris: Skira,

1948), 156. Emphasis in original.

[25] Ibid., 553.

[26] Ibid., 698. Emphasis in original. Malraux uses

this same statement as the epigraph to his final volume on art, L’Intemporel. Cf. also: “Like the

painter, the writer is not the transcriber of the world; he is its

rival.” L'Homme précaire et la littérature 152.

[27] Les Voix

du silence, 570.

[28] Ibid., 879. Cf. “The history of art is the

history of forms invented in place of (“contre”) those inherited.”

Ibid., 582.

This is a paper I gave at the annual conference of the Australasian Society for Continental Philosophy at Deakin University, Melbourne, 7- 9 December 2016.

Absolute reality for us was God; then man. But man is dead, after God...

The aesthetic theories of thinkers such as Hume, Kant, Hegel, and Marx, together with their modern descendants, are still of historical interest, but of historical interest only.

Art creates a world “scaled down to man’s measure” It “wrests forms from the real world to which man is subject and make them enter a world in which he is the ruler”.

The painter, in other words, is first inspired by paintings, the novelist by novels, the poet by poetry, and the composer by music.

In fulfilling a desire to create – to emulate the achievements of the artist or artists he most admires – the painter, composer or poet must therefore, paradoxically, eradicate from his own work all trace of the styles of those very artists.

.... the “fallacy of the neutral style”.

“We are beginning to understand that representation is one of the devices of style, instead of thinking that style is a means of representation”.