THEY'RE A WEIRD MOB: the phenomenon in Australia

In Australia, Sydney's TCN-9 bought the first 52 episodes of The Samurai in March 1964 but did not show them until Monday 28th December 1964 at 3.30-4pm. This was, of course, an English-dubbed version which had been prepared for foreign consumption at the request of Senkōsha Productions by a Miss Rinko Ikeda. She had used any available foreigner - diplomats, businessmen - to supply the voices, though Ōse was dubbed by the only professional actor, American Bill Ross who also dubbed Hayashi Shinichirō in The New Samurai. Ross can be seen in the 1979 film Bushido Blade, a Japanese-American co-production about Commodore Perry's expedition to Japan which starred Richard Boone and Mifune Toshirō and featured Amatsu Bin as a villainous swordsman.

The first story shown out here was actually the second one made, namely Koga Ninjas. The serial was shown five days a week. On 1st March 1965 the timeslot was changed to 5-5.30pm, no doubt due to repeated requests from viewers. After the screening of the last episode TCN had on hand, on 11th March of the same year, they made an announcement asking viewers if they liked the program, if they wanted to see more and what time they would like it shown. Now this is highly unusual in TV stations in this country, especially TCN-9 whose cavalier attitude to viewers is well known - ask any Star Trek fan. It shows how unsure they were about this show. After all, as mentioned earlier, it was the first Japanese TV program to be shown in this country.

The response to that single announcement was, according to TCN, "staggering" with literally thousands of viewers of all ages writing in wanting more. As a result, it returned with new stories on 24th May 1965 at 5.30pm so that more people could watch it. It continued in the 5.30pm timeslot until the end of October 1965 by which time it was going into repeats. At the end of November, it was returned, due to protests when it was taken off briefly, still in repeats as all but the very first story had been shown. It was shown at noon on Sundays with two episodes back to back to try to satisfy the demand. All in all, it was repeated three times in that 12 months due to popular demand and at each showing, it gained ever more fans, making it the most popular show in TCN's history to that time.

The press dubbed it a 'phenomenon' and declared that with "one man, very little money and a couple of television cameras, Japan has achieved a victory over Australia that eluded her militarists two decades ago. Sydney has been conquered, other capitals are sure to fall." Ōse Kōichi's popularity made him something of a pin-up among many fans (though there were those of us who would rather have had Kongō or Genkurō or Kotarō adorning our lockers) and his popularity here was probably equal to that in his own country, relatively speaking.

The two TV magazines we had then, TV Times and TV Week, as well as The Australian Women's Weekly featured illustrated articles on the program. The chewing-gum company, Scanlen's, brought out a set of 72 black and white gum cards of photos from the series. When the backs were placed together, they made a giant black and white full-length poster of Shintarō. These cards remain a valuable record today of the show's visual appeal and a reminder of what it was, despite the fact that the captions are marred by some misidentifcations ("Matsudaira Sadanobu" labelled a master ninja is one that comes to mind) and misromanisations 'Negishi' instead of 'Negoro', 'Kogo' instead of 'Koga', etc.). Misromanisation of names was a feature of some of the TV guides. My favourite was 'Master Ninja Gone Jam' for 'Master Ninja Dogan' which made one think that ninja was into pinching conserves. Another was 'Marishoten' for 'Marishiten' which had unforeseen consequences in that novelist Ruth Manley borrowed 'Marishoten' for the name of her villain in her trilogy of children's books.

Later in the year, towards Christmas, plastic samurai swords and children's costumes came on the market. The samurai swords were rather expensive for what they were. They were cheaply made and in the most unrealistic colours (yellow, red, green and blue blade, hilt and scabbard all the same colour). Their only redeeming feature in my view was the colour photos from The Samurai which were included, particularly as some of them were not in the gum card set such as a full length picture of Fūma Kotarō resplendent in his gold and purple jinbaori (surcoat).

The costumes were made by an enterprising Australian company which had made Annie Oakley costumes and the like. There were two types of costume. One was a black ninja suit which as a bit naff in my view, even at the time. It was like pyjamas and bore only the vaguest resemblance to a ninja's costume, especially as it had white saddle stitching on the edges something which seemed to belong on a cowboy suit. Like the swords, it was a little overpriced. There were also samurai costumes, rather like fancy dressing gowns. The Powerhouse Museum has one of them and there is a photo on their website here. However, these items seemed to be popular around Christmas 1965-New Year 1966 as both swords and suits on little kids were an unavoidable sight (me, I rather wanted the toy Dalek which was retailing for the princely sum of 8/- at a toyshop in Lakemba).. 20, 000 such suits were made between August and December 1965 while 3000 toy shuriken (popularly known as 'star-knives', the translation used in the series) were distributed at schools. (I'm sure the teachers must have been delighted).

Ninja also turned up in locally made commercials. There was an ad for Kellogg's Cornflakes in which Cornelius the rooster transported little Johnny to feudal Japan where he was set upon by some of the cutest cartoon ninja who disappeared in a puff of smoke when Johnny's mother called him.

Finally, theatrical agent Jim McDonald brought Ōse Kōichi to Australia to star in a 90 minute samurai-vs-ninja pantomime. Once again, this was the first time such a thing had been done in Australia.

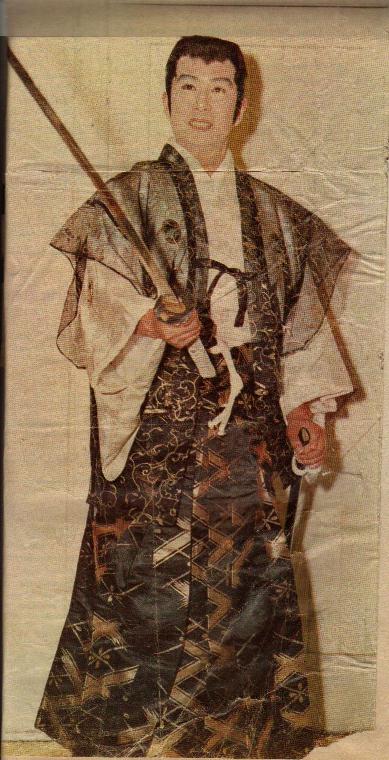

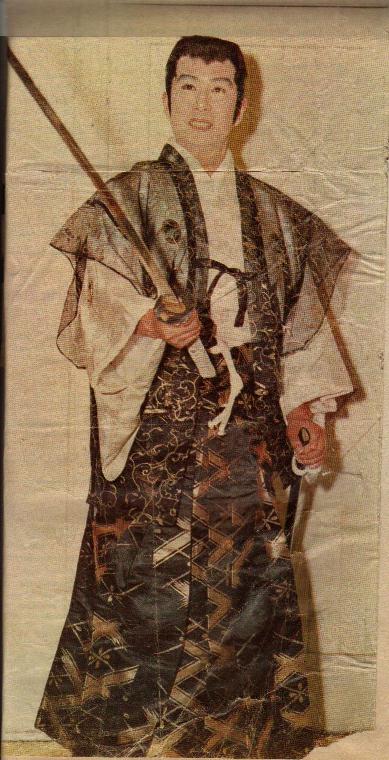

Ōse arrived in Sydney with his dresser and his manager, the latter of whom acted as interpreter from time to time. He arrived on Christmas Day 1965, wearing a rich gold and black silk hakama and haori, ponytail wig, swords and thick, ghostly white Japanese stage make-up in the soaring temperatures of a typical Sydney summer's day when the mercury frequently climbs well above 38° (100° F). He'd made a quick change just before the plane landed (one does wonder how he managed climbing into that get-up, knowing how tiny an aeroplane loo is).

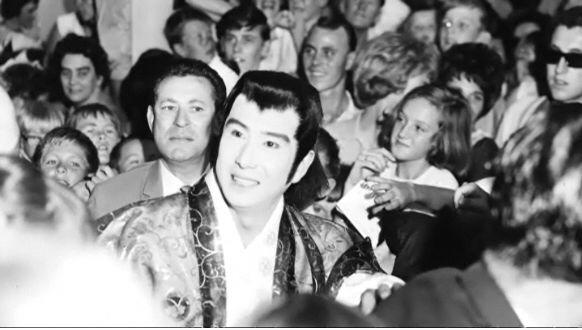

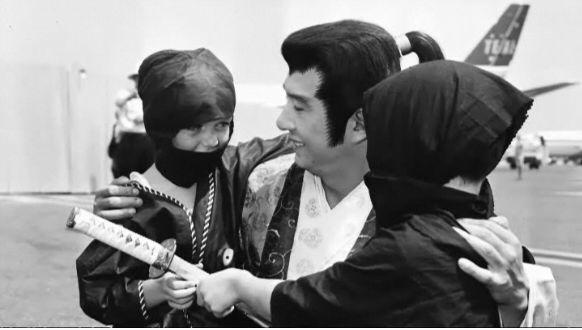

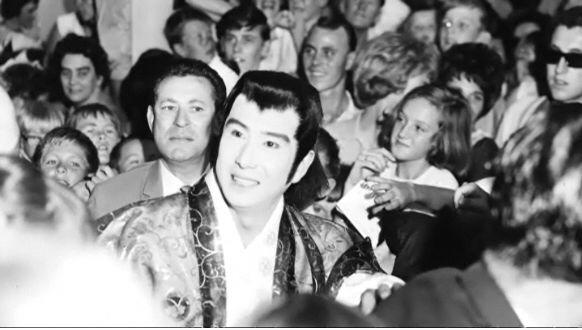

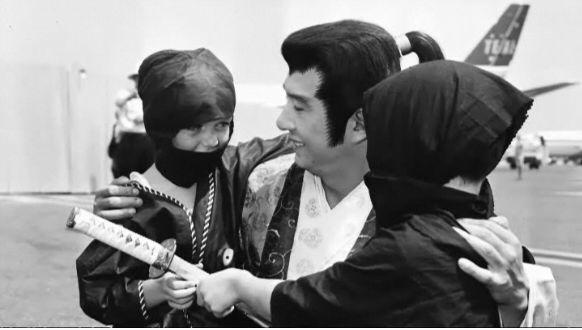

600 fans, many of them in ninja suits, who had waited outside the Customs Hall of Mascot airport for more than an hour, greeted him with cheers. Another 200 waited for him on the roof of the overseas terminal. When he came out of the Customs Hall, dozens of small children who had chanted, "We want Shintarō" for 20 minutes before he appeared, swarmed around him, some throwing paper or cardboard shuriken, and almost knocked him down in their enthusiasm. Some grabbed at his robes or his wig or his sword. He had to be helped clear by six policemen and customs officers. (One might say that Sydney's children had succeeded where countless ninja had failed - they'd discommoded Shintarō). Unable to speak English and unaware just how popular The Samurai was in Australia, he found the experience totally bewildering.

He made another public appearance later, at the Scanlen's gum factory in Sydney where he presented prizes to 10 winners of a Samurai colouring competition, shaking the hand of each and saying, "Sayonara". For this occasion he wore a navy pin-striped kimono as he found his splendid costume and white stage make-up tended to frighten younger children and he didn't want them to be afraid of him. Once more he found the children's enthusiasm bewildering.

Members of the press who met or interviewed the 5' 9" sturdily built star were impressed with his quiet, almost shy manner, his boyish good looks and charm, his sense of humour which came through despite the language barrier, and his politeness and modesty. He said he liked Australia and that he had wanted to come here since childhood. However, he confessed himself amazed that Australian children would like so much such a 'traditional' Japanese story as The Samurai.

The Samurai stage show opened on Monday 27th December at 2.15pm,at Sydney's Stadium at Rushcutter's Bay. The Stadium, venue of boxing matches and many pop concerts, was torn down about 1970 to make way for the Eastern Suburbs Railway overpass, ironically about the same time as the Shōchiku Kokusai Gekijō where the Japanese stage version of The Samurai had appeared. It was a hideous barn of a place, a vast brick heap with a corrugated tin roof built during the Depression of the 1930s and totally un-airconditioned.

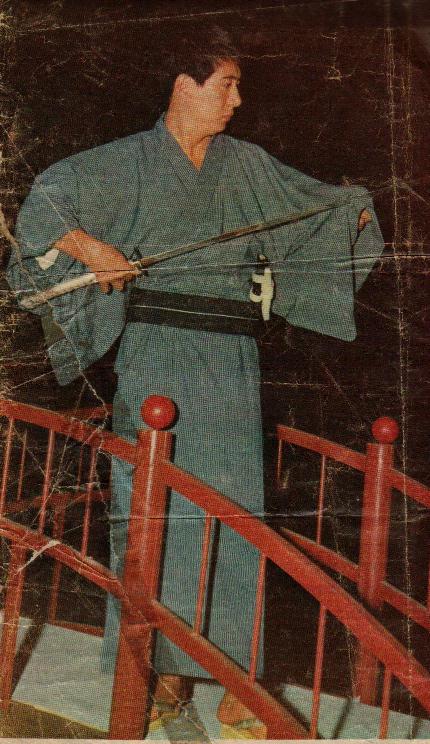

Ōse had to perform in his elaborate costume in 103° F heat or more and that was just the outside temperature.

Within the Stadium it was many degrees more. Several performers portraying black-robed ninja, collapsed off-stage and had to have medical treatment. The comment at the time was it was a wonder Ōse didn't jump back on the next plane to Japan when he saw it. For this stage show it had been rigged with trapdoors, catwalks, platforms and fly-wires so the ninja could make their spectacular flying entrances as per the TV series. It had also been painted to represent something out of feudal Japan.

The stage show ran for 6 days, matinees only, in Sydney and played to capacity houses (the Stadium seated 3,750). It was generally well received by the critics, allowing for the hybrid nature of the beast wherein an attempt was made to duplicate on stage the TV camera's trickery. The plot was a basic one about Shintarō rescuing a princess from some ninja, who were drawn from locally-based Japanese as well as Australian martial arts teachers. There was some disjointedness which made it seem more like a succession of oriental cabaret acts as ninja and dancers each did their "turn". Ōse made three appearances and managed to infuse the proceedings with his customary dignity as Shintarō and to hold attention with his presence and his expert swordplay. He outdrew the Beatles in attendances at the Stadium, averaging 6000 a show, according to press reports (in which case about half must have had to stand in view of the Stadium's seating capacity). This success led to pressure being put on the promoters to take the show to Melbourne.

On the night of 5th January 1966, Ōse flew to Melbourne to a deafening welcome from over 7000 fans. This represented the biggest crowd at Essendon Airport since the arrival of the Beatles, a fact which was even reported in the Japanese press. Essendon has long since been superseded by Tullamarine Airport as Melbourne's major airport. Ōse was in the city for three stage shows (Thursday 6th January-Saturday 8th January, 2.15pm daily,10/- admission for children,19/- for adults) at Melbourne's Festival Hall. Here at these shows his arrival on stage was greeted as enthusiastically as in Sydney with cheering, which he acknowledged with a bow. This caused Melbourne newspapers to join with their Sydney counterparts in declaring Robin Hood, Superman, Tom Mix and Davy Crockett things of the past. All told, Ōse was in Australia a total of 2 weeks before film commitments forced him to return to Japan. Not all his fans were children. Some of the most enthusiastic and unruly at his arrivals and appearances were teenage girls.

The National Library has programs and related material from this stage show in its Ephemera Collection. The catalogue record can be found here.

At the time of his visit there was much talk of buying and showing Ōse's then current TV series, Bakku Nanba 333 (Agent 333) which occupied the 6.30-7pm Sunday timeslot just before The New Samurai in Tokyo, and another samurai-type series he had just completed the pilot for but nothing ever came of this. This was a pity as there were and still are plenty of' samurai-type TV series of equal quality or better than The Samurai.

However, Sydney's ATN-7 bought Phantom Agents (Ninja Butai Gekkō) and screened it at 6pm weekdays, starting 31st January 1966. Each story was told in 2 half-hour episodes. It ran throughout most of 1966 and was expected to topple The Samurai from its perch but failed to do so, perhaps because being set in modern Japan, it lacked The Samurai's special magic and made the ninja's exploits seem too unreal when set in Tokyo's concrete jungle. Moreover, some of those exploits were pure fantasy such as ninja who could transform themselves into cups and saucers. At least what was shown in The Samurai seemed reasonably likely.

Or perhaps the novelty of ninja was wearing off as Australian children, like their Japanese counterparts before them, were swept up in the spy craze of The Man From UNCLE and clones. Nonetheless Phantom Agents was popular enough for one women's magazine to send a journalist to Tokyo to interview the staff and actors from the series while they were shooting an episode. Some young viewers declared they liked it better than The Samurai. But for me, it was a "Clayton's Samurai," or something you watched only when suffering acute withdrawal symptoms and badly needing a 'ninjamono' fix.

TCN-9 then bought The New Samurai and showed it at 5.30pm weekdays from 11th July until 14th September 1966. At least it was scheduled to be shown at that time. However, many episodes in the third story were pre-empted for coverage of the visit of President Lyndon B. Johnson (this was at the height of Prime Minister Holt's "all the way with LBJ" era). Needless to say, we ninja fans were NOT amused. Instead of conflicts in Kyushu we got scenes in Sydney of anti-Vietnam War protesters lying down in front of LBJ's car and the then Premier of NSW telling the driver to "run the bastards over".

Since those palmy days, The Samurai in repeats was treated rather cavalierly by TCN-9 as they would yank it off the schedules without warning and replace it with something nauseating like National Velvet often right in the middle of a story; or they'd show it out of order - when they showed it at all. In protest at this mistreatment, I boycotted TCN-9, refusing to watch any programmes on it, which is how I came to miss Star Trek's first season.

After a brief stint in the early 70s, The Samurai faded from our screens, then was repeated fully in Sydney in Melbourne at the ungodly hour of 6am weekdays around 1977-1978 (just before most people had VCRs). It was then repeated yet again 1979/1980 in the same timeslot but completely out of sequence, whereupon it was removed for about six months then returned with the Kōga ninja series. A few episodes of The New Samurai were repeated in 1981, again out of sequence. When fan Alex Paige (to whom I am indebted for the information about the post-1977/78 repeats) wrote to complain as he had done for the same reason during The Samurai repeats, he received a terse reply, "Thank you for your further letter about The Samurai. Unfortunately, this series can never be repeated."

Presumably the NINE Network (of which TCN-9 is a part) had by then either junked its copies of the series (as so many TV networks in this country did with b/w material around that time), or else they simply fell apart (anyone who has seen some of the later repeats would have noticed how ratty they got over time). A tiny number of episodes ended up in the hands of a private collector who has since released what he has to video in the 1990s. There were rumours that another private individual had the full set and the rights but wanted to charge too much for screening rights but these proved false.

Despite all this, The Samurai still did not entirely disappear. At the 1968 Sydney Royal Easter Show there was a cultured pearl exhibit which boasted regular clashes between a Kōga and an Iga ninja which one could watch. One could have free ninja hats and fans, as well as Japanese food (sukiyaki). For many years in the 1970s there was a well known trotter named Iga Ninja. There are no prizes for guessing the inspiration for that horse's name. A Japanese writer visiting Australia was astonished to find Australian children assuming he could leap tall buildings in a single bound, as it were, like a ninja because that was what all Japanese could do.

Novelist Ruth Manley took names, even characters and incidents from The Samurai and recast and wove them into her three children's novels based on Japanese myths and folklore, The Plum Rain Scroll, The Dragon Stone and The Peony Lantern, in whose pages one will find ninja, Kongō, secret treasures, mirrors which are clues to those treasures, Fūma, 'Marishoten' and so on. They were published in 1978, 1982 and 1987 respectively.

The series still remains a byword. A review in a country newspaper of Kurosawa's film, Kagemusha said it reminded the critic of The Samurai, which would have delighted Funatoko no doubt, and horrified Kurosawa. An article in Melbourne's Age in 1974 describing Japanese TV, spoke of ninja being very familiar to Australian audiences as well. More recently, some Australian martial arts magazines madee half-jesting references to 'star-knives' and The Samurai, especially during the US-inspired ninja craze of the 80s.

The story continues on Gone But Not Forgotten which takes the tale through the 1980s, the 1990s right up til now, taking in anniversaries and the return of Shintaro to Australia..

[Cast & Characters] [New Samurai] [1973 Revival] [Historical Characters Mentioned in The Samurai] [Articles in the Australian Press] [Phantom Agents] [Episode guide - Man From Edo] [Episode guide - Koga Ninja] [Episode guide - Iga Ninja] [Episode guide - Black Ninja] [Episode guide - Fuma Ninja] [Episode guide - Fuma Ninja Continued] [Episode guide - Ninja Terror] [Episode guide - Phantom Ninja] [Episode guide - Puppet Ninja] [Episode guide - Contest of Death] [Introduction] [Historical Background] [The Phenomenon in Japan] [Ruth Manley] [Shintaro documentary] [Gone But Not Forgotten: 1980s to Present][Home]